Home ArticlesLettersArchives Home ArticlesLettersArchives |

Empire Notes"We don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic. We never have been. I can't imagine why you'd even ask the question." Donald Rumsfeld, questioned by an al-Jazeera correspondent, April 29, 2003."No one can now doubt the word of America," George W. Bush, State of the Union, January 20, 2004. A Blog by Rahul Mahajan Not only was the war in Afghanistan not the

best way of capturing high-level al-Qaeda members, it actually

dramatically exacerbated the threat from al-Qaeda and other Islamist

formations. Early opponents of that war made the argument that the

bombing would increase the threat of terrorism. At the time, very few

agreed. In fact, many progressive intellectuals castigated the antiwar

movement for what they considered its reflexive stupidity in opposing

the war. A mere nine months after the beginning of the war, however,

analysts at the FBI and CIA were among those who agreed with the

antiwar movement—although many of the aforementioned intellectuals

still did not. According to the New York Times, in June 2002,

“Classified investigations of the Qaeda threat now underway at the FBI

and CIA have concluded that the war in Afghanistan failed to diminish

the threat to the United States … Instead, the war might have

complicated counterterrorism efforts by dispersing potential attackers

across a wider geographic area.”1

Middle-level al-Qaeda operatives used the opportunity to strengthen contacts with other Islamist groups in the region. The war enabled them to draw these groups, hitherto focused on their own domestic political questions, into the world of terrorist networks opposing the United States—thus dramatically increasing the pool from which future terrorists will be drawn. According to one official quoted, “Al-Qaeda at its core was really a small group, even though thousands of people went through their camps. What we’re seeing now is a radical international jihad that will be a potent force for many years to come.” The bombing of a nightclub in Bali on October 12, 2002, which killed 192 people (nearly all Westerners, with Australians the largest single group of victims), brought the absurdity of this approach to the “war on terrorism” into the sharpest relief. Military policy analysts have understood for years that it is the very predominance of the U.S. military that makes opponents or potential opponents of U.S. policies turn to “asymmetric warfare,” in which that tremendous technological and material advantage can be partially neutralized, as it was on 9/11. The government had acknowledged this fact by that the ‘90s, for example, in Presidential Decision Directive 62:”America’s unrivaled military superiority means that potential enemies (whether nations or terrorist groups) that choose to attack us will be more likely to resort to terror instead of conventional military assault.”2 Clearly, the steps since 9/11 to increase that military superiority even more and to use it more frequently represent exactly the wrong approach, and will dramatically exacerbate the threat of terrorism. The Bali attack is clearly one of the fruits of the Afghanistan war—a suspect in custody has admitted that it was aimed at Americans, not Australians.3 It also represents a significant change in terrorist tactics. Contrary to the popular conception of al-Qaeda as simply ravening to kill Americans any chance it gets, the organization had never previously gone for easy “soft” targets. The list of attacks either by al-Qaeda—two U.S. embassies, the USS Cole, the World Trade Center and Pentagon—shows a pattern of hard targets that symbolize U.S. power, involving difficult preparation and people willing to commit suicide. The Bali nightclub was a soft target of no particular symbolic value. Suspects reportedly said that senior al-Qaeda members, meeting in Thailand in January 2002, “decided to turn from embassies, which were becoming better protected, to so called soft targets like resorts and schools.”4 Thus, the war on terrorism reaches its reductio ad absurdum—more military prowess leads to more terrorist attacks, more defense of hard targets leads to more attacks on soft targets, and it is simply impossible to defend all soft targets. Footnotes

1. "Qaeda’s New Links Increase Threats From Far-Flung Sites," David Johnston, Don Van Natta Jr., and Judith Miller, New York Times, June 16, 2002. 2. "Combating Terrorism: Presidential Decision Directive 62," May 22, 1998, available at http://www.nbcindustrygroup.com/0522pres3.htm. 3. "Suspect Tells Police that Target of Bali Bombing was Americans, not Australians," Jane Perlez, New York Times, November 9, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/09/international/asia/09INDO.html. 4. Bali Bomb Plotters Said to Plan to Hit Foreign Schools in Jakarta," Raymond Bonner with Jane Perlez, New York Times, November 18, 2002. Rahul

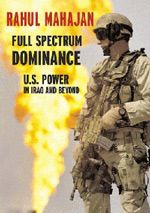

Mahajan is

publisher of Empire

Notes. His latest

book, “Full Spectrum Dominance: U.S. Power in Iraq

and Beyond,” covers U.S.

policy on Iraq,

deceptions about weapons of mass destruction, the plans of the

neoconservatives, and the face of the new Bush imperial policies. He

can be

reached at rahul@empirenotes.org.

|

Bush

-- Cracks in the

Ice?Perle and

FrumIntelligence

Failure Kerry

vs. Dean SOU

2004: Myth and

Reality Bush

-- Cracks in the

Ice?Perle and

FrumIntelligence

Failure Kerry

vs. Dean SOU

2004: Myth and

Reality |